Crossing the Line – Part 1

So where do I start?

Perhaps with the people who made me and brought me up. We were a small family. I am an only child of parents who were both

the only child in their families.

I only knew one of my grandparents. The others were all dead before I was

born. And for the first 8 years of my

life I hardly saw him either. He was so

totally different to my parents (or so it appeared) that it was sometimes

difficult to believe that they had anything in common.

A while ago, I remember doing one of those rather frivolous

on-line quizzes which are supposed tell you something about yourself. In a few questions, this one purported to

reveal what social class you were, and my result was “Solidly Working

Class”. I laughed. I am a clergyman, educated at Oxford, from an

independent school, born of a vicar and a teacher. Surely you can’t get much more middle class

that that?

But as a thought about it, I also remembered that my parents

were not from middle class homes, far from it, and neither were their

parents. Perhaps this frivolous quiz was

revealing something about me which I had not identified before? Perhaps I was more working class that I realised?

|

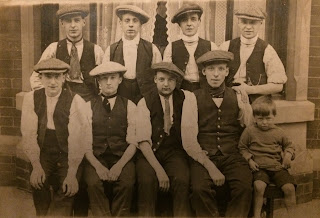

| Grandad (back left) with friends before the War |

My grandad was staunchly working class, deeply proud of his

Lancashire working man’s values. My

parents had climbed the social ladder.

They had moved beyond their working class roots, aspiring to something

more refined.

He lived in a rented bedsit in the same neighbourhood in

Bolton where he had always lived. We

lived in a huge Victorian vicarage with a tennis court, bluebell wood, orchard and

rose garden. Our vicarage had old servant’s

quarters in the attic which were bigger than his entire home.

He was a man of few words – preferring to keep his thoughts

to himself most of the time. He smoked

40 cigarettes a day and collected his Embassy tokens for treats or presents from

the catalogue. My parents were always

talking – their jobs required it – and hated anything to do with smoking.

He loved working with his hands and the tool bench which he

had made, contained the tools of his trade.

When my dad had become the first person in the family ever to go to

university, grandad made him a beautiful desk out of old ammunition boxes. By the time he had finished, no-one would have

guessed the wood’s former purpose and today the desk is where I often go to

write sermons or blogs, having been passed down to me, by my father in turn. It still shines with that deep dark lustre of

mahogany that has been lovingly worked to perfection.

He also made radios, and other ‘modern’ gadgets. He did the whole thing, from designing the

circuits to combining the components and making the cabinet which housed

them. I remember one in

particular. It had something like a

liquid crystal display above the tuning dial with two glowing bars which came

together when the radio signal was strong and drifted apart as the signal

faded. “To find the best signal” he

would say, “you tune the radio until the bars are as close to each other as

they can get”. It was like magic to me.

When I was seven he gave me a model railway – not in a box,

but laid out on an enormous table with a station, goods yard, village and level-crossing. It was like my own small version of Legoland

but made in wood and metal, and painted with loving care.

When I was about 8, ill health brought him to live with us,

and he made a 36” racing yacht for me, engaging me to help him at every

stage. I remember being given the awesome

responsibility of pouring the molten lead into the mould he had made for the

keel. I remember him showing me how to

steam strips of wood so that they would bend around the frame he had made to

form the sleek lines of a racing hull.

These were the things he had done with my dad when he was a

child – model train sets and racing yachts were the pinnacle of their

relationship, but my father had left these far behind as sixth form led to

university, and then on to theological college and ordination.

That is not to say that grandad didn’t have his faults. He could be deeply moody and his few words

could move almost imperceptibly to sullen depression at the drop of a hat. His dark moods could last for days when he

would shuffle around in a world of his own, speaking to no-one.

When he came to live with us for the final 5 years of his

life, his smoking drove my mother mad, and his working class pride was the

antithesis of everything she aspired to.

It wasn’t that her upbringing had been pretentious or snobbish – far

from it. In many ways it had been

significantly harder than my dad’s. Her

father had been an unskilled, alcoholic labourer in Sheffield. Work was casual and unreliable, and when he

did get paid, he would drink the money on the way home before beating her

mother savagely. My mum had a childhood

characterised by poverty, fear and malnutrition in the slums of Sheffield and I

don’t know if she would have survived but for the kindness of a local

prostitute who used to give her money for chips. Where grandad enshrined working class

dignity, she only knew working class misery and she had fought with everything

she had to leave it far behind.

Perhaps the reason they clashed so often was that he

reminded her of the things she had escaped from. He didn’t drink, but his room was always

thick with smoke. He would watch ITV -

she watched BBC. She had a modern

cylinder vacuum cleaner – he loved his old upright Hoover and he would tell me

over and over again how and why it was different and better than these modern

plastic gimmicks. He was content to sit

quietly in his chair in his room with his ashtray and his telly. He didn’t care if he was on his own, and

resented coming downstairs to family meals.

She wanted to go to dinner parties, talk to educated people, and develop

her career to get as far away as possible from the origins which he continued

to represent.

And when he got

moody, he really got moody. I am sure

that part of the reason for building model train sets and yachts with my dad,

was to avoid really talking to him. He

was a very guarded man who had seen almost everyone he loved die, and he had

built a wall around his heart to stop it ever being broken again.

After his early 20’s were stolen in the trenches of the

First World War, seeing his friends and comrades die, he was one of the very

few of those who enlisted early to return home.

He then married but his wife died after giving birth to my dad. He withdrew within himself more and more. Then my dad almost died when he was 2 years

old from an ear infection. He was only

saved by his grandmother taking him out of hospital when they had given up on

saving him, slowly loving him back to life.

He did eventually allow himself to love again,

but could not show it, because his love was for his wife’s sister, also widowed. The taboos which remained about such

relationships were still strong in his community – when he was born it was

still illegal to marry your dead wife’s sister and it was expressly prohibited

in the Prayer Book. Although that

changed in 1907, the stigma and disapproval of such relationships was still

strong, and it was only after the death of his mother-in-law many years later that

they dared to express their love and get married. She then died only 3 or 4 years later.

I suppose that his job as a tram driver suited him for that

very reason. Isolated in his cab, he

could just get on with life without having to engage with other people. He simply got the tram from A to B and back

again as the world went on around him. I

think he started on the horse-drawn omnibus, moving to electric trams with the

advent of new technology. But when the

trams were replaced by buses, he was unwilling to make another technological leap

by learning to drive. Instead he became

a bus conductor for the rest of his working life. I can imagine him as a character in the TV

comedy “On the Buses” – suspicious of change, proudly working class, resentful

of authority, and resistant to anything which would threaten his fragile status

quo.

As a child, I do remember that whenever I got too close –

whenever I started to penetrate the wall which he had erected around his heart

– he would quietly distance himself again, not in a cruel or manipulative way,

but to shore up his self-defence.

He died when I was 13.

The smoking finally got him and he had a stroke, aged 81.

After 3 months of an air purifier running non-stop in his

room 24 hours a day, it still smelled of stale cigarettes, and when we took the

pictures off the wall, they left clear rectangles like oases in the darkening

layers of tar and nicotine which surrounded them.

Yet I learnt so much from him about enduring adversity and

about retaining the right kind of pride & dignity, no matter what anyone

else thought.

I still have the yacht.

The train set went when I was a teenager because I needed money and

space for a settee and a hi-fi. But I

still have the yacht we made. When I

look at it, I see a man who took pride in what he did – a man who was self-contained

and resilient – but also a man who cut himself off from others out of fear of

getting hurt again.

My grandad drove a tram.

|

| Grandad, mum and me |

(With Thanks to Sam Emms for the title graphic - thanks Sam!)

Click here for an Introduction to Crossing the Line

Click here for an Introduction to Crossing the Line